The Marvin Quadrant: Better Sitcoms-- from The Dick Van Dyke Show to Better Things

Previously on A Life in Television: “One way to understand the ‘process revolution’ of the 1970’s/1980’s might be by analogy to episodic television’s shift to what I’ll call arc television. What the discipline has come to describe as ‘current-traditional’ rhetoric reduces writing to discrete episodes while also reducing components of writing to episodes of a sort—this is citation day, this is transition day, this is paragraph day. Every day the same, each component containable in a single episode of the same length and tone.” “Arc television requires investment over time, as does process-based writing and writing as life work.” ("Episodes and Arcs," Sept 2022).

“Consider the challenges of world-building when writing in an episode mindset. The boundaries of the episode provide structure while imposing limits on invention, especially in terms of scope—the story must be told completely in a short time. Now consider the opportunities of world-building when writing from an arc mindset—infinite possibility (isn’t that the nature of writing, from word choice and sentence structure to range of reference and connection). In arc writing we work within the sprawl and potential of ourselves in relationship to a burgeoning world, making choices that create a version of the world for a rhetorical purpose. Everything relates/connects to everything else. Formulas give way to leaps of intuition and the play of possibilities.”

Watch these clips of the opening credits of these two television shows, first several from the five seasons of The Dick Van Dyke Show set to showbiz/music hall tunes and then the montage of Sam Fox and her daughters from the opening seasons of Better Things set to John Lennon’s “Mother”; I also include a scene from the Season Two finale featuring three generations of the central family’s women dancing for eldest daughter Max on her birthday. Please note a few things about the rhetorical worlds introduced in these sequences: the initial separation of the work and family spheres in the first Van Dyke opening sequence giving way to the blending of the two spheres in later openings, when work family comedy writers Buddy and Sally appear in the Petrie living room; the choice of music; the use of montage; and the prominence of performances of different types (domestic, workplace, and professional) across the two shows. In relation to previous A Life in Television entries, keep in mind that the classic situation comedy offers episodes while the contemporary example offers an arc.

When Rob Met Laura

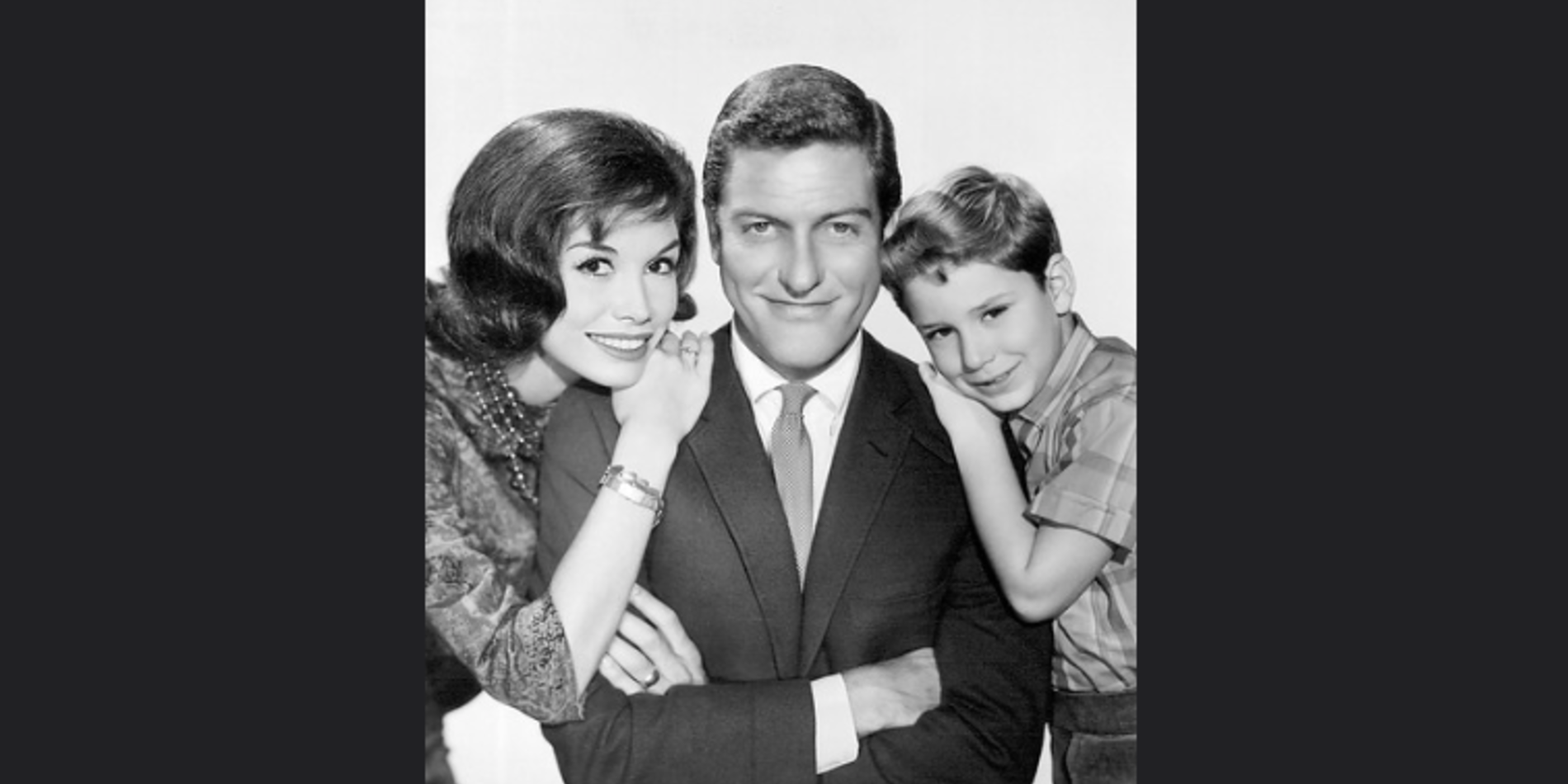

Carl Reiner created The Dick Van Dyke Show (1961-66) but didn’t play the lead role, one he originally developed for himself in an earlier pilot called Man of the House, in which he played comedy writer Robbie Petrie. Instead, on the series that eventually aired, Reiner played Alan Brady, the egomaniacal host of the variety show for which Van Dyke’s Rob Petrie served as head writer in the shtick- and invention-packed New York City writers’ room shared by Rob, Buddy Sorell (Morey Amsterdam), and Sally Rogers (Rose Marie). (In one memorable episode, Reiner played eccentric painter Sergei Carpetna, whom Laura commissioned to paint her portrait as an anniversary gift for Rob—she posed in a favorite outfit but Reiner’s maniacal, my-vision-comes-first Carpetna rendered her in the nude, leading to a plot in which Laura and Rob have to negotiate with the painter to ensure the painting would not be displayed—you can find some Carpetna episode dialogue here.)

In both shows—the pilot that died and the variant that lived—the general set-up drew from Reiner’s experience as a co-star on Sid Caesar’s Your Show of Shows (1950-54), which featured a legendary writers’ room of Mel Brooks, Neil Simon, Danny Simon, Mel Tolkin, Lucille Kallen, Selma Diamond, Joseph Stein, Michael Stewart, Tony Webster, and Reiner himself. The Van Dyke show brought to prominence the parallel settings of workplace and home (though there were glimmers of this dual engagement with home life and work life in I Love Lucy and some radio shows that featured characters in show business), with scenes alternating between the New York City writers’ room and Rob and Laura (Mary Tyler Moore) Petrie’s home in New Rochelle, where they raised son Richie and kibitzed with neighbors Millie and Jerry Helper (Ann Morgan Guilbert and Jerry Paris).

When Laura Left Rob

The Mary Tyler Moore Show (1970-77) later copied this structure, alternating between Mary Richards’s workplace at the Minneapolis television station (her work family of Lou the Editor, Murray the Writer, Ted the Anchor, Gordy the Weatherman, and nemesis Sue Ann, the Happy Homemaker) and her apartment (Rhoda Morganstern in place of Millie Helper and Phyllis Lindstrom providing some antagonist energy). Rob’s Alan Brady Showwriters’ room gives way to the more varied jobs of the WJN newsroom, with Mary as the producer holding the team together: Murray writing at the adjacent desk, Lou presiding from the hidden sanctum of his office, Gordy sauntering affably through the desks, Sue Ann appearing to deliver pointed barbs at Murray, and Ted braying cluelessly as a talentless doofus reincarnation of the egomaniacal (though talented) Alan Brady. Indeed, in the concluding episode, when the television station has been sold and only Ted keeps his job, Mary tearfully pays tribute to her work family, telling them explicitly that they have been her family, which leads to a group hug (and an awkward amoeba-like shuffling toward Mary’s desk for tissue as they all cry, even Mr. Grant, who lives on as the title character in a newsroom drama spinoff with another workplace family—you can watch the whole final episode here, with the final scene beginning at 19:00).

Other notable primarily workplace/work family sitcoms include Cheers, Taxi, and Barney Miller through The Larry Sanders Show and The Office and currently Abbott Elementary, while primarily home family/domestic sitcoms span the pioneers Father Knows Best, Leave it to Beaver, and My Three Sons through All in the Family and The Jeffersons followed by the also New York-set Friends and Seinfeld and recently Modern Family and The Goldbergs, while a show like The Big Bang Theory keeps the parallel genre going, with scenes at Cal Tech and at the characters’ apartments. You television-watchers likely have favorites of your own in these genres.

Sam Fox (not Sam Malone)

Better Things (2016-2022), created by and starring Pamela Adlon (co-creator Louis C.K. left his role as an executive producer after the second season), claims a distinctive place in this situation comedy genealogy (although one can find parallels with One Day at a Time, which aired from 1975-84, with a Netflix reboot from 2017-20), dramatizing Adlon’s character’s Sam Fox’s home life as a single mom raising three daughters (Max, Frankie, and Duke) with Sam’s mother Phil living next door; Sam also continues her long career as an actor navigating a range of jobs across L.A., the setting of the show. Like Reiner, Adlon draws on her life in show business, which began in 1982 (her father Don Segall produced and wrote for television and her mother Marina, like Phil, came from England). In rendering Sam’s work life, rather than locating the show in a writers’ room like the one shared by Rob, Buddy, and Sally, the scripts follow Sam all over L.A. and beyond as she does voiceover work, acts, and directs at various times across the 52 episodes. At home, the show often features extended, wordless scenes of Sam preparing family meals in the house’s kitchen, highlighting the solitary creative work of keeping a family nourished and together. The episodes rarely have linear, problem-to-solve, bruised-feelings-to-soothe plots; they tend to present and explore situations, rarely resolving. The maturing of the daughters provides the overarching movement of the show (along with Sam’s constant efforts to find work and maintain connection to her daughters as well as a wide circle of friends, many in showbiz); all three daughters go through recognizable stages of growth, questioning and rebelling, alternately craving connection with and pushing away their mother, fluctuating wildly in mood and affect in a way parents probably understand better than I do. Ultimately, Better Things steadfastly observes and explores the dynamics between a mother and her daughters and her own mother, refusing to turn any into types. The adventures large and small of the daughters as they grow and define their identity in the world, and Sam’s parallel work and parenting careers provide two of the many pleasures of the series.

Lessons from Rhetorical Situation Comedy—Writers’ Rooms, Invention, and Family Group Performing

Let’s consider the rhetorical situation of the writers’ room Rob Petrie shares with Buddy and Sally, a compact stand-in for the writers’ room of Your Show of Shows (lovingly reproduced in the 1982 film My Favorite Year, executive produced by Mel Brooks). The exigence each week stems from the need to produce material for that week’s show. Rob, Buddy, and Sally engage in invention, bouncing ideas off each other, sometimes performing the kernels of bits (watch from roughly 1:20 to 4:00 in this episode for a glimpse of comic invention in this idealized writers’ room); they riff and revise on the fly, deadline always looming. The first episode of the series includes the three comedy writers performing at a party at Alan Brady’s house (with Laura pointing out earlier that Brady invites them solely for the “spontaneous” performances—legend has it that Reiner and Brooks’s 2000 Year Old Man bit grew out of such social events when the writers performed for the expectant audience ); thus the first episode establishes both the domestic and workplace contexts as well as a public performance akin to a short, fast-paced variety show with each of the three genres getting some time in the spotlight. Better Things features performances as well, like the birthday dance linked earlier; Frankie in one episode performs spoken word poetry, and often domestic life takes the form of performance, as when the family performs a funeral service over Sam and Duke. Ultimately the series puts forth Fox family life as a site for invention enacted in performance.

The Writers’ Room as Model for the Writing Classroom

Let’s consider different kinds of writers’ rooms in relation to the writing classroom. Perhaps the most familiar writers’ room in the university context resides in the creative writing workshop, whether at the undergraduate or MFA level. Think of the contrast many students (and perhaps many of us) draw between academic writing and creative writing. Students often keep their creative writing to themselves, guarding their privacy and also likely keeping their innermost writing selves safe from critique and readers’ expectations. Thus one of the potential shocks of initial creative writing workshop experiences—who are these people telling me what they think I should do with my poem or story? Who is this teacher telling me there are “rules” and “genre expectations” and audiences to consider for poems and stories—I thought those were just for academic writing, where I don’t expect to be allowed to be creative.

What if we can recast all writing, academic and creative and any other kind, as acts of rhetorical invitation?

Of course the workshop, at least in my experience, falls into the same trap as episodic television, with the piece of the moment and the discussion of the day decontextualized; while purportedly the workshop offers a deliberative moment aimed at future action, all too often the forensic and ceremonial dominate, with judgment of past action or the praise/blame nexus embracing the living writing before the group. Given the individualistic, isolated-writer ethos of creative writing instruction (unless things have changed dramatically since my MFA days), workshops do not function as collaborative sites of invention. A writers’ room workshop would need to address issues of the individual imagination as well as the purpose of the workshop itself as aimed at future action and perhaps the writer’s arc of development. This kind of arc-oriented workshop would ask each reader to locate the work in the writer’s work beyond the immediate piece or, as writers get to know each other’s work, in relation to genre and the reader’s experience of the work-in-progress. When I taught fiction workshops, I divided students into groups of three or four to read with each other through the entire course—many suggested that they would benefit from getting feedback from more readers; I responded that I wanted them to give this model a try, as their other workshops would likely feature full class response. I also asked readers to stay away from the language of “like” and “don’t like” or “works” and “doesn’t work” in favor of describing their experience of reading in relation to the elements of plot, character, and setting; this approach sets aside even the deliberative, future-action dimension I usually put in the foreground in favor of emphasizing reader experience of the writer’s invitation.

How would this work in a PWR classroom? You might already steer your students in these ways for peer review sessions, asking them to describe their reading experience in relation to key elements of the essay draft. We might also consider borrowing the first rule of improv, “Yes and,” for both peer review and also for group writing activities. In the context of peer response, "Yes and" aims to build on what the writer has offered in the draft rather than shift direction or course correct (or correct in any way). In the context of group writing activities, many of us might already use group invention activities, for example crowdsourcing rhetorical elements of a text as a foundation for rhetorical analysis or small-group thesis generation. How about group-writing a paragraph or full draft with a "yes and" prompt guiding students to build on what their peers write? While students generally write their own essays in PWR and other courses (with some group writing projects in Engineering WIM courses), these activities can highlight alternatives to the individual writer working in isolation as well as the premise that peer review must put criticism (or reductive praise) in the foreground. While students likely don’t watch sitcoms or know much about writers’ rooms by that name, we can ask them to share the contexts in which they’ve written or created collaboratively with a "yes and" approach.

Rhetorical Situation (and) Comedy

I’ve long wanted to develop a comprehensive theory of comic rhetoric and have come to realize that such a theory is neither possible nor necessary. Instead, I’ve settled on a set of key comedic principles and strategies, chief of which is the principle that comedy often flows from making connections between things that haven’t been connected before (an offshoot of incongruity theory, one of the Big Three explanations of the source of comedy along with superiority/assertion of status and catharsis/release of suppressed fears in many books on comic theory); this principle translates to the comic strategy of creating connections and inviting the audience to share the insight generated by the new connections. Considered from this perspective, the RBA (maybe all academic writing) becomes a comic genre—the RBA writer’s task boils down to creating new connections among sources in order to create new understandings of the issue or problem to share with the reader (is this what we mean by originality in the RBA?). While the RBA generally doesn’t aim to solicit laughter, it does aim to build insight and understanding in the reader, much as comedy does. The RBA—a comedy of connection, without the laughs.

What can we borrow from situation comedy working from this premise? The RBA as a genre builds a world within an academic genre of research-based argument. Building the world involves engaging with sources as well as selecting what makes up the world, drawing on sources along with the writer’s experiences, observations, and critical and creative faculties; individual readers engage with the presented world of the essay, which doesn’t necessarily follow from the writer’s rendering of the world (parallel to an audience not getting a joke, an explicitly comic invention). What does a series like Better Things, drawing on Pamela Adlon’s life experiences and observations of the entertainment industry, offer the viewer? Family relations as a series of performances, sometimes familiar rituals (family meals), sometimes incongruous (the funeral for Sam and Duke). The RBA features many ritualized elements—what incongruities can RBA writers introduce and resolve for the reader through creating new connections?

Have a story idea or experience you'd like to share? We'd love to hear from you! Please consider pitching an idea for a PWR Voices feature to Newsletter Editors Nissa Cannon ncannon@stanford.edu and Kevin Moore kcmoore@stanford.edu.