ATS Annex: Negotiating Concerns with Student Data Privacy in the New Academic Year

By Jenae Cohn

I’ve been glued to Twitter this summer. Perhaps you have too. You see, it’s been my space to process the seemingly interminable churn of heartbreaking 2017 news. In some ways, a space like Twitter with its stream of wisecracking punditry might make current events feel even worse than they really are. But for me, it has provided a refreshing community of worrywarts (like me) to sound off with the ultimate antidote to atrocity: humor.

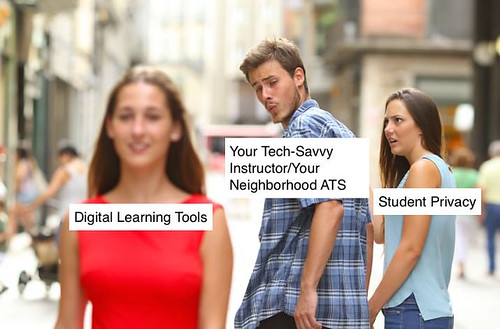

In fact, one of my favorite memes from the summer is “the distracted boyfriend” meme, which takes a stock photo of a man getting a glimpse of a woman faded in the foreground with his girlfriend staring up at him in distaste.

![]()

It’s honestly the perfect stock photo for a meme: the situation is clear, the conflict potent, and the visual rhetoric of “the other woman” blurred out and cooly unaware of the man’s adoring gaze is about as delicious as stock photo plots get. So, this image gets repurposed and captioned with something like this (this particular iteration is courtesy of Twitter user @MazMHussain):

So, what does this have to do with academic technology? Or PWR? Well, this meme got me thinking about educational technology and higher education’s often fraught relationships to it. We tend to lust after its possibilities, considering how hip and attractive it is to use the latest gadgetry. After all, so much of our latest technology allows us to track, store, and analyze student data in unprecedented ways, which could give us a clearer picture of how our students interact with course content and material. Not only that, but getting our students working, thinking, and engaging online can get them that much more aware of public audiences and the ways in which their work could have a larger impact on the world. It’s enough to make any of us raise our eyebrows and let out our own little “check-THAT-out” whistle. It might, in fact, start to look a little something like this (this one is courtesy of me):

So, the girlfriend here is “student privacy” because that is my biggest worry as an ATS who really, really wants to recommend the technologies and solutions to help your students become digitally literate citizens of the world. Let me be up front about this: as writing instructors, I strongly believe that we need to help students understand the implications of composing and circulating knowledge in digital environments. Otherwise, we run the risk of our media becoming invisible and, in turn, opting out of mindful choices about how to compose the most effective content for a digital environment. Composing digitally requires that students adopt some new literacies: writing for the Web is largely about curating sources and reaching a target audience. If we’re going to help students do that, we need to have them working and thinking in our now ubiquitous digital spaces.

But there’s honestly a lot for our students to worry about with their futures, and the last thing I want to encourage anyone in our program to do is to adopt tools that might jeopardize our students’ rights to their own personal information and ideas. Whenever a student publishes something in an app or in a program that is not owned by Stanford University, we run a certain risk of a company profiting off of that data (and selling it to advertisers). But that’s the world of the Internet now: everything we contribute to a social network or a public forum is pretty much getting monitored and tracked by profiteering third parties. Does that mean we stay offline? No. Certainly not. But it does mean that, as instructors, our job is to remain vigilant when we investigate new technologies and, in turn, to educate our students about what the implications are of composing and consuming content in digital spaces.

So, what do we do? How do we make sense of the complicated choices that we have to make about which tools and technologies we expose our students to? If we are wanting our students to compose in new spaces, how do we have them do so safely? How do we give them options for learning in these spaces without exposing them - and their identities - to a world that is exceedingly greedy for their data?

I don’t have answers for all of these questions, but I do have some things that I’d encourage writing instructors to think about when adopting and innovating with digital tools in their classes this year:

-

Weigh the pros and cons of using Canvas (our learning management system) and third-party tools. The chief advantage to putting your course content and having your students interact in Canvas, our online learning management system here at Stanford, is that all of the content posted there is safely protected on Stanford’s servers. Because you and your students have to log in to Canvas with SUNet IDs and passwords, no one from the public can access any of that information. Plus, there is a lot of great teaching stuff you can do in Canvas: you can post and share content, you can create class Wikis, you can facilitate class discussion forums, and you can create mini-ePortfolios. That said, you may purposefully want your students to be engaging with a broader public (or you may desperately have functionality you need that is not covered in the Canvas ecosystem), which takes me to…

-

Be explicit with your students about WHY you’re using third-party tools and what the implications of using those tools are. Part of our jobs as educators is to help students understand that when they compose content for the Web, their work doesn’t just disappear into cyberspace; it lives on servers (if they’re composing in the cloud) or on hard drives (if they’re composing in software installed on their machines). This is important to writing because effective writing also doesn’t exist in a vacuum; the places where we publish our writing necessarily impact what we’re writing and when we’re writing it. So, educating ourselves on what the third-party tools and doing and how they work will help our students also better understand the implications of their participation in particular activities and with particular tools.

-

Give students options for using certain tools, particularly if they come from third-party software. Not all students will feel equally as comfortable with adopting certain tools. Allowing any engagement with third-party tools should be strictly optional and, therefore, should likely be tied to low-stakes assignments where students needn’t worry about the effects that opting out might have on their overall course grade. When you conceive of an assignment that might involve the use of a third-party tool, think through the alternatives and what options different students might have.

-

Develop a curiosity (and excitement!) about trying new tools. I realize I might be scaring you a little bit about third-party tools. They’re not all bad. Really. I use Google Docs all the time, for example, which is the quintessential third party tool where I know that my data is being sold (spoilers: there are web crawlers scanning Google Docs all the time, which means that Google can target things “I’m interested in” based on what I’m composing). Honestly, Google Docs still functions best for a lot of the composing activities I want to do (both for myself and for my students). So, how do I reconcile my knowledge of privacy intrusion with the functionality of the tool? I make the conscious and educated choice to use it, knowing that I probably should not store anything too sensitive, personal, or inflammatory in the space. As an extreme example, I’m not storing any documents in Google Doc that have my social security number in it. In other words, I use Google Docs for certain kinds of teaching and learning activities and, all the while, offer caveats to my students so that they can make mindful choices about what they may (or may not) want to compose in a space like Google Docs.

This may be a lot to think about at the start of the quarter, but as I learned from educator Bonnie Stewart in her keynote at the Digital Pedagogy Institute (a conference I attended this summer), one of our most important tasks as 21st century educators is to develop, in her words, “collective awareness” of the risks and the benefits of composing in online environments. She ended her talk with a call for working harder to understand the structures of the society that we’re in. Digital literacy is one big, big way to do that.

Let’s take a look at the “distracted boyfriend” meme one more time:

![]()

I think something a little subversive about this meme is that the “other woman” in red and the girlfriend in blue are nearly identical; they almost could be the same model. The woman in red as doppleganger to the woman in blue therefore offers the even more complicated and hilarious counterpoint that perhaps the thing that the distracted boyfriend lusts after is the thing that he has right next to him the entire time. If we use digital learning tools mindfully, and aim to most often use ones that protect student privacy and data, perhaps we can really get it all: innovative thinking and learning without limits. I mean, maybe this explodes the meme a bit as it suggests that the boyfriend should carry on with both of these women in his life (I’m not promoting infidelity, I swear!), BUT THE POINT IS, I think it is possible to have our cake and eat it too when it comes to digital learning and protecting student privacy.

But hey, I’m just starting a conversation here. Come chat with me. Make an appointment to meet with me. Ask me to give a workshop to your students. Check out the materials I've produced online for PWR. You are not in this alone. Online learning is all about community. Care to join me?